PaperCranium on Nostr: via saifedean nostr:note1aa74mfvw8l7h0lzh2leuavmjf8cflu8cgux2jdx4hfu53juzkauswx5369

via saifedean (npub1gdu…6nak)

quoting note1aa7…5369Javier Milei One Year Assessment

Everyone excited about an Argentina economic miracle is basing it on all sorts of government statistics except the most important statistics: money supply measures and public debt growth.

Under its new supposedly free-market Rothbardian president, Argentina's money supply in 2024 has increased at these astonishing rates:

M0: 209%

M1: 133%

M2: 93%

M3: 123%

To put these numbers in perspective, note that they dwarf the rates during the preceding years, during which Argentina thoroughly earned its reputation as one of the most dysfunctional fiat monetary basket cases in the world.

In the four years of 2020-2023, Argentina’s money supply measures grew at a compound annual growth rate of:

M0: 50%

M1: 77%

M2: 90%

M3: 86%

pop

In Milei’s first six months in office, public debt grew from $370 billion to $442 billion, a staggering increase of 19.4%. Borrowing $72 billion in 6 months can make any economic statistics look good, but the problem of course is in the long-term consequences. It is possible to make short-term growth, poverty, unemployment, or inflation numbers look good by printing and borrowing money, thus transferring the cost of a short-term glow up to the future, where they are paid with exorbitant interest. Those of us who thought things could not possibly get worse might need to reconsider.

Remember that in his election campaign, Milei specifically campaigned on a platform of abolishing the central bank, even saying that that was non-negotiable. Yet as soon as he went into office, all such talk was ignored, and replaced with elaborate stories about how shutting down the central bank would be very politically unpopular. In this, Milei has fully adopted the same statist rhetoric that is always used to justify inflation by governments: the short-term pain of stopping inflation would be so bad, that it's better to continue down the path of inflation and ignore the long-term consequences. The reality is that the Argentine central bank is bankrupt, and the sooner this reality is acknowledged, the quicker it can be overcome. Trying to save the central bank can only be done by piling up debt obligations that will make the future problems even worse. In this, Milei is no different from all his predecessors who sought short-term relief at the expense of the future.

Milei has also refused to default on the public debt, which would have been the Rothbardian solution to finally free his countrymen from eternal debt slavery to pay for the consumption binges of their previous presidents. A default on foreign debt, and a shuttering of the central bank would have caused a few months of painful adjustment, after which the Argentine economy would recover on a solid footing, without even the possibility of a government being able to create inflation or saddle the population with debt. Foreign currency and bitcoin would likely dominate such an economy, and the state would necessarily be limited by the fact that it cannot print money.

By not shutting down the central bank and letting it ramp up its money printing, Milei is sowing the seeds for currency crises in Argentina’s future. By not defaulting and hiring the same bankers who brought calamity to the country in the previous administrations, it seems Milei is eager to get another IMF bailout, which will saddle Argentinians with generational debt slavery and more fiscal crises in the future. Unsurprisingly, he is raising taxes significantly, illustrating that his understanding of Austrian economics is no deeper than the regurgitation of cliches on TV. To increase taxes in order to facilitate more government borrowing is a crime against the people of Argentina to benefit the international banking cartels and the IMF criminals. It is a tyrannical recipe advanced by the Keynesians at the IMF, and has no relation whatsoever to what any real economist worth his salt would advocate.

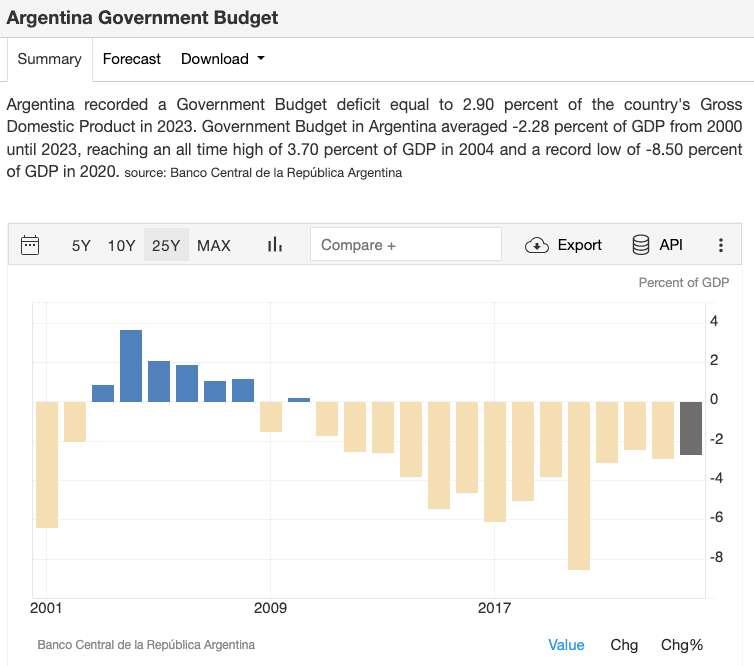

A lot has been made about Milei reducing the budget deficit, but this is not that important. Argentina’s problem was not that it had a big budget deficit, as its budget deficit has usually been pretty low, under 4% of GDP, the same range as European countries with no major inflation and fiscal problems. The problems have always been in money supply increase and in public debt, both of which have accelerated under Milei in an unprecedented way.

The cherry on top is that Milei has shipped off the little remaining gold Argentina has to London, in search of some yield. Pawning off a politically neutral monetary asset free of counterparty risk in search of a few quick bucks does not inspire confidence. In his book The Ascent of Money, historian Niall Ferguson details how Argentina’s economic problems began when president General Juan Domingo Peron visited the central bank in 1946 and was astonished at how much gold was sitting there. Argentina had more than 1,000 tons of gold at that time, and Peron and his successors would not resist the temptation to finance their spending by running down the gold reserves that should have been backing the people’s money. The past 8 decades of calamity were the predictable consequence. After billions of percentage points in inflation and countless defaults, Argentina’s gold reserves today are no more than 61 tons. By shipping off the last monetary reserve of the future in exchange for a quick buck to allow him to keep paying off debt so he can get another IMF loan, Milei has completed Peron’s inflationary legacy to its logical end. Argentina now has no money of its own, only an ever-growing pile of liabilities from foreign banks replete with political and economic risks. Rothbard must be turning in his grave every time this Peronist invokes him to justify his actions.

This data is astonishing and flies in the face of the hype. But unless someone can show me why this data is wrong, then, for all of his libertarian and free market rhetoric, Milei is a vintage Latin American populist inflationist, buying short-term popularity with long-term inflation and debt, essentially no different from every Argentine leader since Peron. All that his free market rhetoric seems to have achieved is to trick poor Argentines into trusting their broken central bank again instead of trying to find a working alternative like Bitcoin. His anti-socialist rhetoric is nice to listen to, and his hysterical antics, relentless emotional crying, and triumphant theatrics may be amusing to some, but fate usually serves its cruelest dishes to those who celebrate before victory.