John Carlos Baez on Nostr: I love reading about the medieval physics: you can see people struggling against ...

I love reading about the medieval physics: you can see people struggling against mental traps, often failing, but still putting up a fight. We shouldn't laugh at them: theoretical physicists may be stuck in their own traps today! Good new ideas often seem obvious in retrospect... but only in retrospect.

For example: Aristotle argued that a vacuum is impossible, because the velocity of an object equals the force on it divided by the resistance of the medium it's moving through. A vacuum offers no resistance - so an object would move through it at infinite speed!

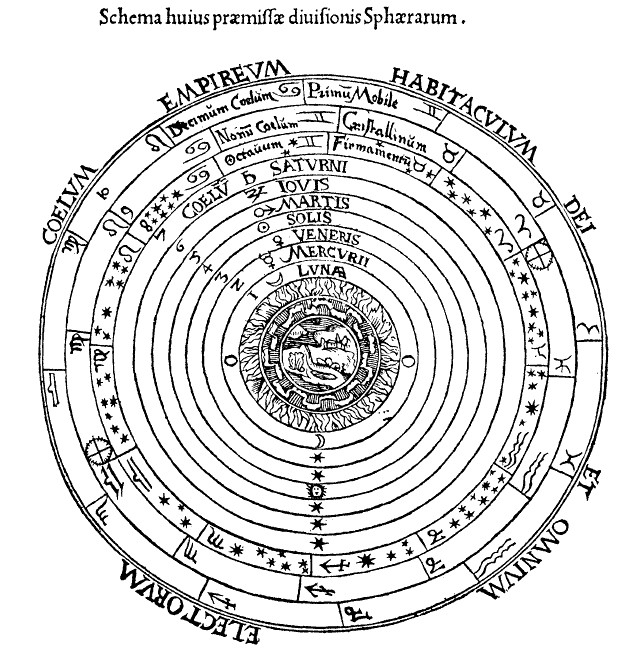

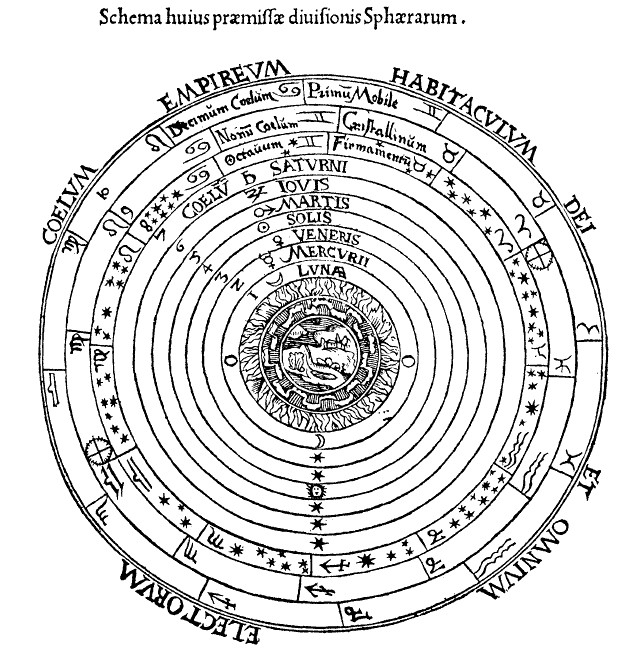

Around 1100, the medieval Arab physicist Ibn Bajja disagreed. He argued that the celestial spheres - i.e. the planets and stars - move at finite speeds even in the vacuum. So, he said, we should 𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑡 the resistance of the medium from the object's natural speed, not 𝑑𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑑𝑒 by it.

Averroes fought back, agreeing with Aristotle. Later, Thomas Aquinas sided with Ibn Bajja. By the 1300s, most Western natural philosophers had sided with Aristotle.

There are definitely problems with the subtraction theory. What if the resistance exceeds the force? Does the object move 𝑏𝑎𝑐𝑘𝑤𝑎𝑟𝑑𝑠? But back then they didn't know about negative numbers! So maybe proponents of the subtraction theory would say an object 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑠 𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑙𝑙 if you push on it with insufficient force to overcome the resistance.

(1/2)

For example: Aristotle argued that a vacuum is impossible, because the velocity of an object equals the force on it divided by the resistance of the medium it's moving through. A vacuum offers no resistance - so an object would move through it at infinite speed!

Around 1100, the medieval Arab physicist Ibn Bajja disagreed. He argued that the celestial spheres - i.e. the planets and stars - move at finite speeds even in the vacuum. So, he said, we should 𝑠𝑢𝑏𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑡 the resistance of the medium from the object's natural speed, not 𝑑𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑑𝑒 by it.

Averroes fought back, agreeing with Aristotle. Later, Thomas Aquinas sided with Ibn Bajja. By the 1300s, most Western natural philosophers had sided with Aristotle.

There are definitely problems with the subtraction theory. What if the resistance exceeds the force? Does the object move 𝑏𝑎𝑐𝑘𝑤𝑎𝑟𝑑𝑠? But back then they didn't know about negative numbers! So maybe proponents of the subtraction theory would say an object 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑠 𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑙𝑙 if you push on it with insufficient force to overcome the resistance.

(1/2)